By PAUL BENNETT (AIMS Author)

- Troy Media, 27 February 2018

The days are numbered for Nova Scotia’s seven English language school boards. Since the release of Avis Glaze’s Raise the Bar report, defenders of the existing order have rallied behind the status quo and claimed that eliminating ‘elected’ board members spelled the end of local democratic governance.

The latest AIMS policy study, Re-Engineering Education, challenges that contention and proposes a significantly better alternative – the decentralization of decision-making and the establishment of autonomous school-community governing councils.

Regional school boards have been disappearing in Atlantic Canada, one province at a time, over the past twenty years. Elected board members in Nova Scotia are the last ones standing.

School boards, as constituted, provided a façade of local democratic participation. Shielded by a strict corporate governance philosophy, the six elected boards outside of Halifax were formalistic in operation, run by veteran ‘boardies,’ archaic in their rules, and dismissive of parent, community, and municipal concerns.

Elected board members at the Halifax Regional School Board worked harder at listening, but were constrained by provincial law that essentially limited them to closing schools and redrawing school boundaries. Good intentions and patching up the existing model were not the ultimate answer to the erosion of democratic accountability.

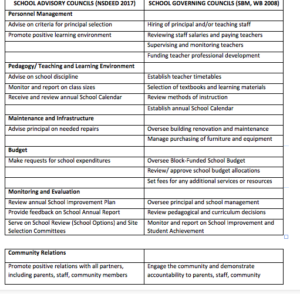

Glaze’s proposed reorganization plan, the Regional Director Model, got it half-right. The new framework clarifies who is in charge, removes the school board barrier, and vests more authority and responsibility in newly appointed Regional Directors of Education. It is too fuzzy in describing the enhanced role to be given to School Advisory Councils (SACs).

Appointing a provincial education advisory committee, consisting mostly – it now appears – of former school board chairs and members, will prove unequal to the task of curing a chronic accountability and democratic deficit.

The proposed replacement for elected boards has a missing piece. No minister of education or government department can successfully provide a direct link to each and every school community. He or she cannot be on top of every community’s local needs, nor directly oversee local officials or principals. Without a change in the plan, it is likely that decision-making will fall, by default, to layers of senior bureaucrats still resident in the seven remaining district offices.

AIMS’ latest study presents a six-point plan to clear away the remnants of the existing SACs and rebuild a more robust model of local involvement and governance that can later be aligned with a new network of district education development councils.

A more effective, accountable and responsive plan would embrace the following structural changes:

First Stage – for Immediate Implementation

- Replace elected regional school boards with a school-based governance and management system, composed of School Governing Councils with parent, municipal, business and post-secondary education representation;

- Establish School Governing Councils with expanded authority in ten specific areas, including setting school priorities, developing and overseeing a school budget and improvement plans, a defined role in the hiring and reassignment of principals, ordering of textbooks and resources, holding regular school policy forums, and producing annual community accountability reports.

- Contract English school district administration in Nova Scotia to four ‘administrative units,’ serving Halifax Regional Municipality, Cape Breton, Central Chignecto, and Annapolis/Southwest regions;

- Establish joint district consortia for the sharing of services, including financial, facilities, transportation, and purchasing services;

Second Stage – Developmental Phase

- Develop and implement District Education Development Councils, composed of a majority of regional trustees, representing elected School Governing Councils, and including appointed members from municipalities, local business, and universities/colleges;

- Reinvest cost savings into enhanced school resources, school-community development and designated ‘education improvement zones’ to address inequities at the school-community level.

Successfully restructuring education requires a longer-term plan for school governance reform, administrative leadership development, and a broader community school development strategy. Implementing such a plan may well take three to five years if the goal is to establish a model that is effective and sustainable. Decentralize decision-making, phase out school boards and take the time to get it right.

Paul W. Bennett is Director of Schoolhouse Institute, and author of “Re-Engineering Education: Curing the Accountability and Democratic Deficit in Nova Scotia” published at AIMS.ca